Hidden in Plain Sight, The Old Jewish Cemetery on the Lido, one of the many islands of Venice, Italy

Story and Photos

by Lena S. Keslin

It’s interesting how some memories can stay with us for many years. In 1984 I came across a deserted Jewish cemetery on the Lido. The old stones inscribed with Italian and Hebrew were leaning over and partially submerged in the murky water of the lagoon. One name caught my attention, Argenti, similar to Argento, the name I used while living in Florence, Italy a decade earlier. It wasn't until 27 years later that I learned this intriguing place was a deserted section of the Old Jewish Cemetery.

The New Jewish Cemetery photos © 2024 Lena S. Keslin

It was the end of November 2011 on a beautiful autumn day when my husband Michael and I went in search of the Jewish cemetery on the Lido. It turns out that there are two. The New Jewish Cemetery which began in 1774 is still in use. It is situated on a hilly, grassy area where there are large trees and pathways that lead to the burial grounds. The cemetery is organized by century and near the entrance there are a some very old gravestones that caught my attention. It was fortunate that we met the caretaker, Artemio Tagliapietra, who suggested we also see the Old Jewish Cemetery, Beit HaChaim. Founded in 1386, it is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Europe. It is open by appointment only so we immediately called Aldo Izzo, the guardian of the ancient cemetery, who at the designated time met us in front of the locked iron gates.

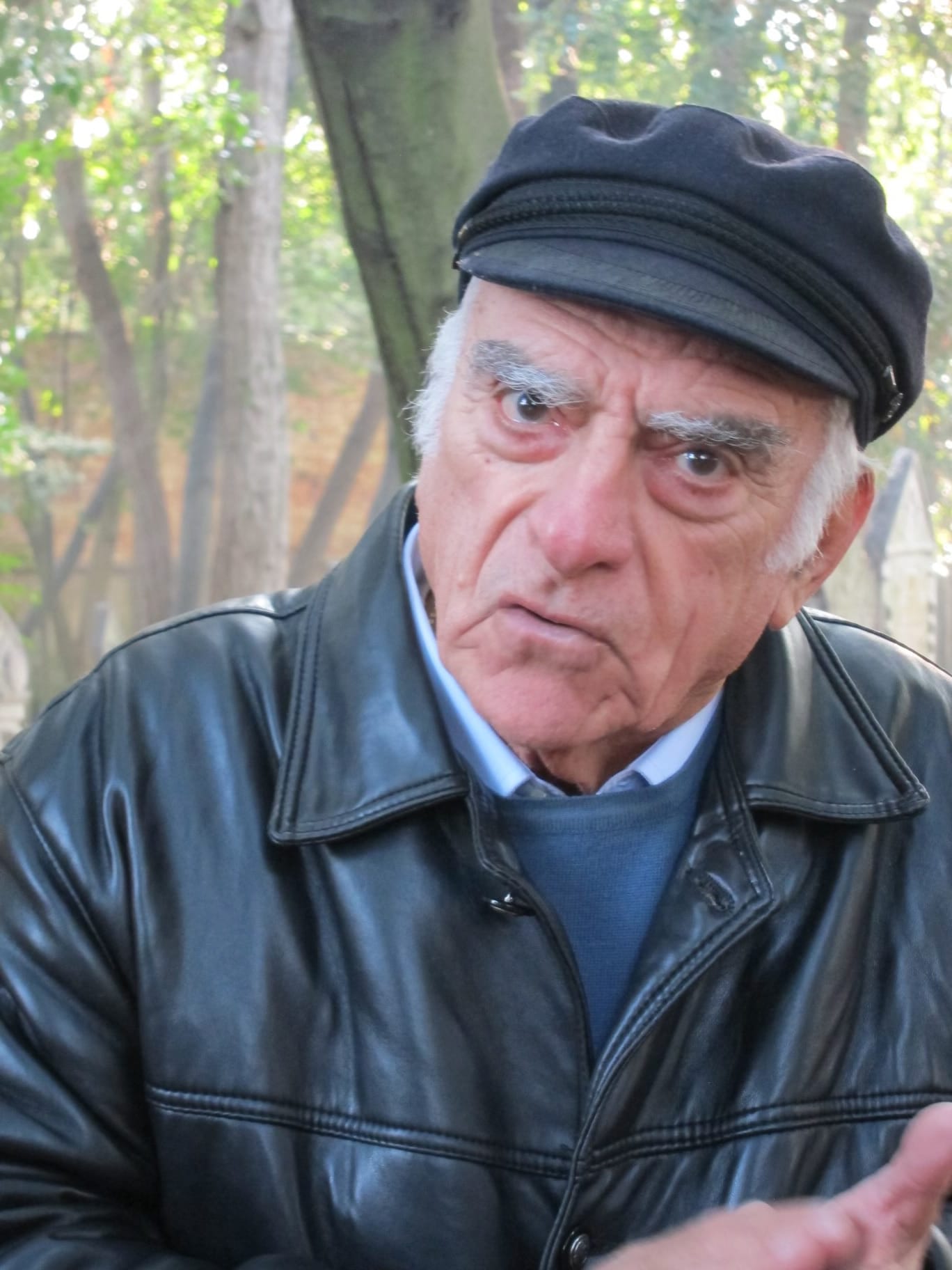

Guardian Aldo Izzo at the Old Jewish Cemetery photos © 2024 Lena S. Keslin

Aldo arrived on his old bicycle, a strong-looking man in his early 80's. I immediately liked this stylish, masculine-looking gentleman dressed in his Italian black leather jacket and cap. There was an intensity in his expression and when he spoke he captivated us with his intelligence and knowledge. At the time I didn't realize the importance of the person we were meeting. I hadn't understood his full commitment and passion, that he along with a group of people have spent many years restoring and organizing the ancient cemetery. In the 40 years since he retired from being a captain of merchant ships, Aldo was now navigating the deceased on their final voyage by water from Venice to the Lido. His work at both cemeteries honors the nameless as well as the known Jewish individuals who made the Lido their last voyage. As a sea captain he was used to keeping records and logs as he traveled the world. He has used the same discipline to organize the graves and stones of his fellow Venetians. He has cataloged the names of the deceased so that they are remembered and his work has made their ancient burial holy again.

Beit HaChaim, the House of the Living photos © 2024 Lena S. Keslin

With Aldo as our captain, we navigated the perimeters of the cemetery. Beit HaChaim translates to the House of the Living, signifying that the soul never dies. Our journey through that revered space made me understand the significance of the eternity of the soul. He showed us different stones and symbols of the Kohanim and Levite, of the tribe of my grandfather.

The autumn leaves were falling to the ground and onto the ancient graves inscribed with Hebrew. The late afternoon light streamed in through the treetops. Brown dried leaves covered the ground of this sacred place and softened our footsteps as we tread our way through it.

Aldo was telling us how Goethe, the German poet and scientist, wrote about his experiences here in 1786. There were also the American writers James Fenimore Cooper and Herman Melville who used their experiences on the Lido in their writing. The English Romantic writer and poet, Lord Byron, might have been describing this cemetery when he wrote,

There is pleasure in the pathless woods, There is a rapture on the lonely shore, There is society, where none intrudes, By the deep sea, and music in its roar: I love not man the less, but Nature more.

Lord Byron, as well as Percy Bysshe Shelley and John Keats were all emotionally taken by their experiences of riding horseback in this desolate cemetery and used that inspiration in their writing. What was it that inspired them? Was it something like the light I experienced? What were they thinking as they callously rode horseback there in the early 1800's trampling on the graves of an outcast people. The only remnants of the Venetian Jews who once were the merchants and money lenders, now just souls marooned forever on this strip of land surrounded by the sea.

Today very little remains of the original ancient cemetery. It is only one seventh the size of what it was. There are 1400 tombstones in a half acre of land. Many of the buried bodies do not have their headstones as time has often misused this holy ground. As we walked the perimeters with Aldo we learned that a Jewish cemetery has the same sanctity as a synagogue. A sacred space where the soul is intertwined with the body so that the spirit and soul find eternal peace and rest.

I'm not sure l'll ever get to meet Aldo again. But, meeting him and experiencing Beit HaChaim with him was something I will never forget. There are moments in our lives that stand out. Perhaps I too have become a keeper of memories.

I remember Aldo calling to me to listen as he had more stories to tell. I have never again experienced such a mystical feeling as that shaft of light falling upon ancient graves covered with autumn leaves. My photographs are a visual reminder of the places I've seen and the people l've met along the way. They captured that experience we had being in the ancient Jewish Cemetery on the Lido, hidden but in plain sight.

Venice was built for defensive purposes on an archipelago, a group of 118 small sandy islands situated in the Venetian Lagoon, an enclosed bay between the mainland and the Adriatic sea. [ed.]

At the time cemeteries were always located outside the city centers. Jews were assigned by the Republic of Venice a desolate sandy strip of land on the Adriatic Sea, known as St. Nicholas of Lido , or just the Lido. A monastery located there claimed it as their own. Finally in 1389 the monks came to an agreement and the Jews had their cemetery.

By 1516 the number of Jews had increased to 700 and the Republic ordered the Jews to live in the area where there were metal foundries . Metal in Venetian dialect was getto but when the German Jews arrived they changed the term to ghetto. The Jews were forced to live in the world’s first ghetto. There were temporary quarters for visiting Jewish merchants in the Ghetto Vecchio and the permanent residents were housed in the Ghetto Nuovo. It was closed off at night from six in the evening to noon the following day. Guards surveyed the area by boat.

The Jews could practice their religion in relative freedom in one of the five synagogues. There was a German or Ashkenazi Synagogue , a Leventine Synagogue for Jews from the Middle East, an Italian Synagogue and the Canton Synagogue and a Spanish Synagogue.. The highest number of Jews in the Ghetto was the year 1630 when they numbered 2868. 454 Jews died during the plague of 1630 -1632. It wasn’t until 1797 that Napoleon ended the enforced segregation of the Jews.

However, in 1938 fascist racial laws took away their civil rights once again. In September, 1943 Italy went against Germany, and the Nazis began an organized hunt for Jews in Venice. The number deported and killed is listed as 246, and only 7 returned. There is a monument to their memory in the New Ghetto.

- L. S. Keslin

Lena S. Keslin is an artist and writer in Santa Fe.

Photos © 2024 Lena S. Keslin. All rights reserved.

Return to HOME or Table of Contents

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

Single Event Announcement:

Save our Jewish Cemetery

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2024-2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.