Rabbi Dr. Raphael Zarum Questioning Belief: Torah and Tradition in an Age of Doubt Review by Ron Duncan Hart

Rabbi Dr. Raphael Zarum has written a book of major importance for contemporary Jews who are critical thinkers. Those who have read Baruch Spinoza, Moses Mendelssohn, or any of the myriad Jewish philosophers since the Enlightenment may be left questioning the biblical narratives in Genesis and Exodus and some of the laws in Leviticus. Did Moses’s staff really turn into a serpent? Does God really want us to slaughter animals in the Temple and what about burnt offerings? How do we understand these teachings of the Torah in the twenty-first century? Rabbi Dr. Zarum is trained as an astrophysicist and a rabbi, giving him a unique perspective in understanding and explaining how to navigate this modern paradigm of belief and doubt. He is the Dean and Rabbi Sacks Chair of Modern Jewish Thought at the London School of Jewish Studies and is an important scholar interpreting Jewish life and being in the modern world.

Rabbi Zarum starts by pointing out that the European Enlightenment led to a dramatic shift from a belief-based perception of reality drawing on a heritage of Biblical teachings to a science-based perception based on empiricism and logical analysis. Enlightenment philosophers from Spinoza to Voltaire moved beyond the personal, anthropomorphic God found in the Torah to a more abstract, cosmic élan vital or life force. For some people, this dramatic restructuring of religious ontology has been threatening, and the reaction has been to shut down questioning and turn belief into absolutism.

Rabbi Zarum begins the book pointing out that a literal reading of the Creation story in Genesis holds logical contradictions as we look at it from the point of view of science. For example, the Creation story says that the sun was not created until the fourth day, but science tells us that the sun predated the earth by millions of years. Centuries of rabbinic thinking from Saadia Gaon to Maimonides and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has pointed out that the Creation story is more than literal narration. It is an exploration of truth. Rabbi Zarum points out that religion and science are partners in our understanding of the world, not identical twins. Religion is humankind’s understanding of purpose and meaning in life, and science is our documentation of what we can observe. He concludes that religious search is the primary driver and shaper of scientific inquiry.

Rabbi Zarum goes on to ask critical questions of belief. Has evolution made Genesis redundant? Does the Flood Story Still Hold Water? Did the Exodus Really Take Place? In each case he interweaves the biblical narrative with rabbinic interpretations and known scientific data to balance what we know and what we believe. We start with biblical narratives that provide us with a basis of belief to understand and explain the world, then like tree rings added each year, we add observable knowledge onto the belief. With incremental progress we build up our belief/knowledge paradigm century upon century.

Sometimes belief and ethics collide, and Rabbi Zarum addresses the Torah teachings on the ethics of slavery. Only days after being freed from servitude in Egypt, the Hebrews and Moses receive laws about the treatment of their own slaves. Slavery was common in the ancient world, the Torah does not forbid it, but it does give restrictions and establishes the rights of slaves. The Torah provides the starting point for the control of slavery, and over the centuries that would lead to its eventual elimination. Rabbi Zarum takes it further to question modern forms of abuse of workers. Some humans will be abusive, and their abuse needs to be controlled by the larger society.

Biblical practices bring other practices into question ethically. Animal sacrifice and the accompanying practice of meat eating are pervasive in the Torah, raising the question about the respect for life. Rabbi Zarum points out that animal sacrifice was used in the Torah as a religious ritual to replace idol worship, which was common in the ancient world. After centuries in Egypt the people had become accustomed to idols, and as they moved out of Egypt animal sacrifice was a ritual replacement for the idol worship with which they were accustomed. The smoke of a burnt offering ascending into the sky would be pleasing to the One, Invisible God in Heaven.

An important ethical issue historically and continuing in our contemporary world is collective punishment. When one person or a collective of persons commit villainous acts, can it be justified to punish the entire family or community they represent? This question becomes poignantly relevant in contexts of violence or war. When a Palestinian stabs an Israeli to death, is it ethically justifiable to destroy the family house of that person, leaving the rest of his family without a home? In agreement with the Talmud Rabbi Zarum concludes that a person may receive punishment for their own evil deeds but not for those of another person.

An ethical question confronting Jews is whether being the chosen people of God is racist or at least discrimination toward others. Since we place high value on equality and social justice in the liberal democracies of the Western world, how do we, as Jews, understand this conundrum of being set aside as God’s chosen people? Some rabbinic sources interpret this as being the result of Abraham and the Israelite people initiating the choice of the One God, who in turn chose them as a special people. The Kuzari and the Zohar each saw Jews as being a special people, blessed by God. Then, Rabbi Zarum suggests that Jews were chosen to serve, to be a light unto nations, engaged with the world, and the potential of all peoples “to seek and to find meaning, morality, and spiritual value.”

Historically, the belief in God has been the ultimate enigma. In Judaism and Christianity scholars have sought to prove the existence of God or the nature of the divine. Much of Jewish prayer is the attempt to define our relationship to God and to imagine the nature of God. Rabbi Zarum goes on to say that the existence or nature of God cannot be defined by miracles, physics, or metaphysics because God cannot be defined. God is not a fact so much as a search, giving us purpose and meaning for life. He says, “In finding ourselves, we find God.”

God is not a fact so much as a search, giving us purpose and meaning for life. He says, “In finding ourselves, we find God.”

Yet, in the Torah we find Abraham and Moses arguing with God, as if God were a human-like being with existential arguments and speech to communicate them. Religious argument has a central role in Jewish life, and the Jewish commitment is to argue with the essence of God that is within us as we search to challenge the social injustice and pain we see around us. The Hebrew word emuna means belief, and it carries the further meaning of faithfulness, a “steadfast commitment and enduring reliability” to community. Emuna is more about our identity, our affiliation, more than a statement of creed. It is not about what we profess in words but what we do in our lives. Our ongoing lives are our emuna, the glue that makes the Jewish people and forges togetherness.

As we struggle through our questions about God and the Torah, the central practice of Jewish life is prayer. Jewish worship is tefilla, prayer, guided by the Siddur, the book of prayer, in a shul, the house of prayer. The luah, the Jewish calendar, defines the times for prayer. The Torah does not define what prayer should be even though it is central to religious life in the rabbinic era. Prayer is faith spoken, it is Jewishness explored and affirmed. It is engagement with our emuna, our spiritual essence.

Questioning Belief: Torah and Tradition in an Age of Doubt is a book about questions and questioning. It is about the DNA of the Jewish people, and how spiritual meaning is interwoven with ethics and social justice. I recommend Questioning Belief as a challenging guide for people who question and seek answers in the Torah that go beyond the literal reading of the texts. Rabbi Zarum opens the door to thinking about Jewishness as a work in process, a continuum that starts with the seven days of creation and comes up to the present in the life of each Jew who questions.

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include these advertisers:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

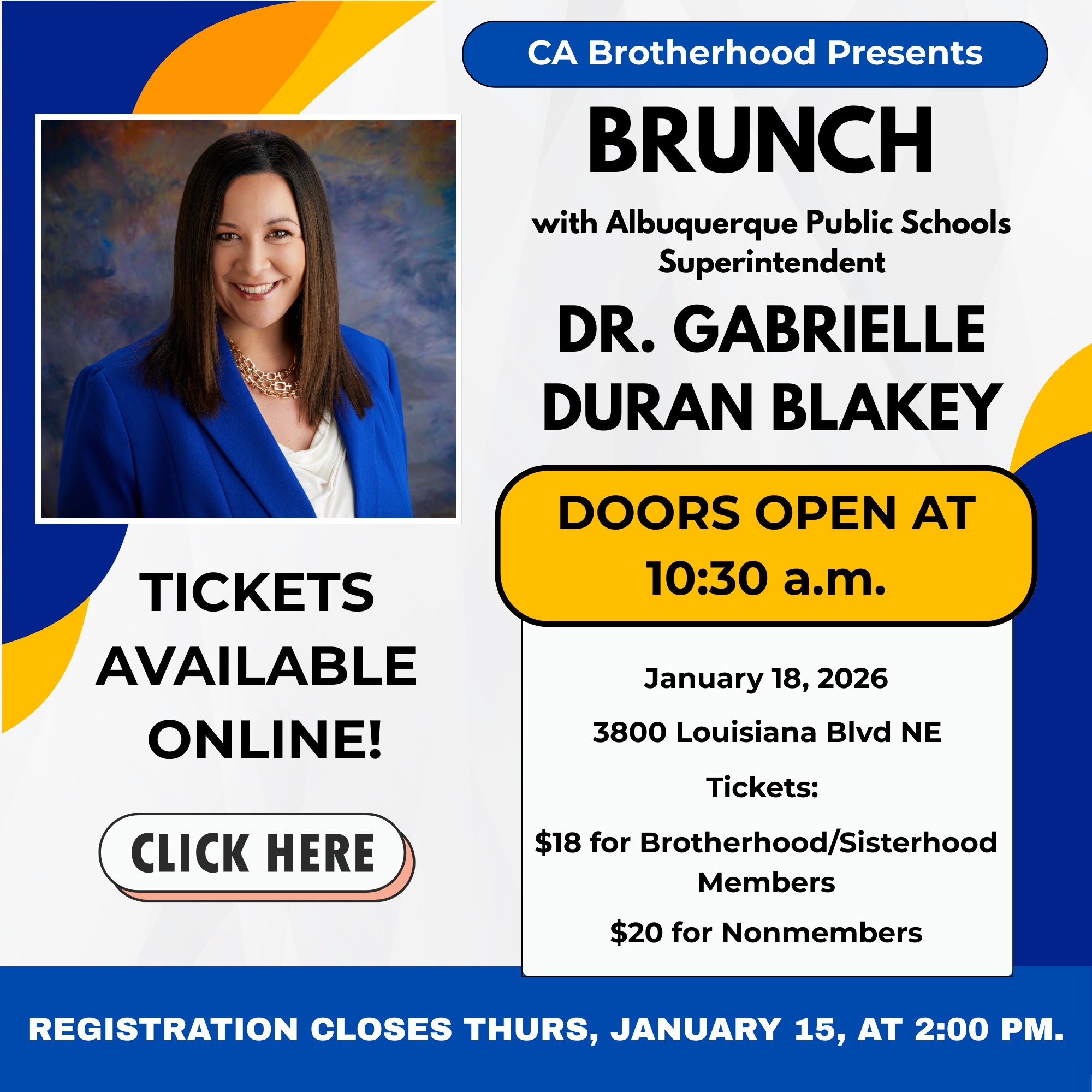

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

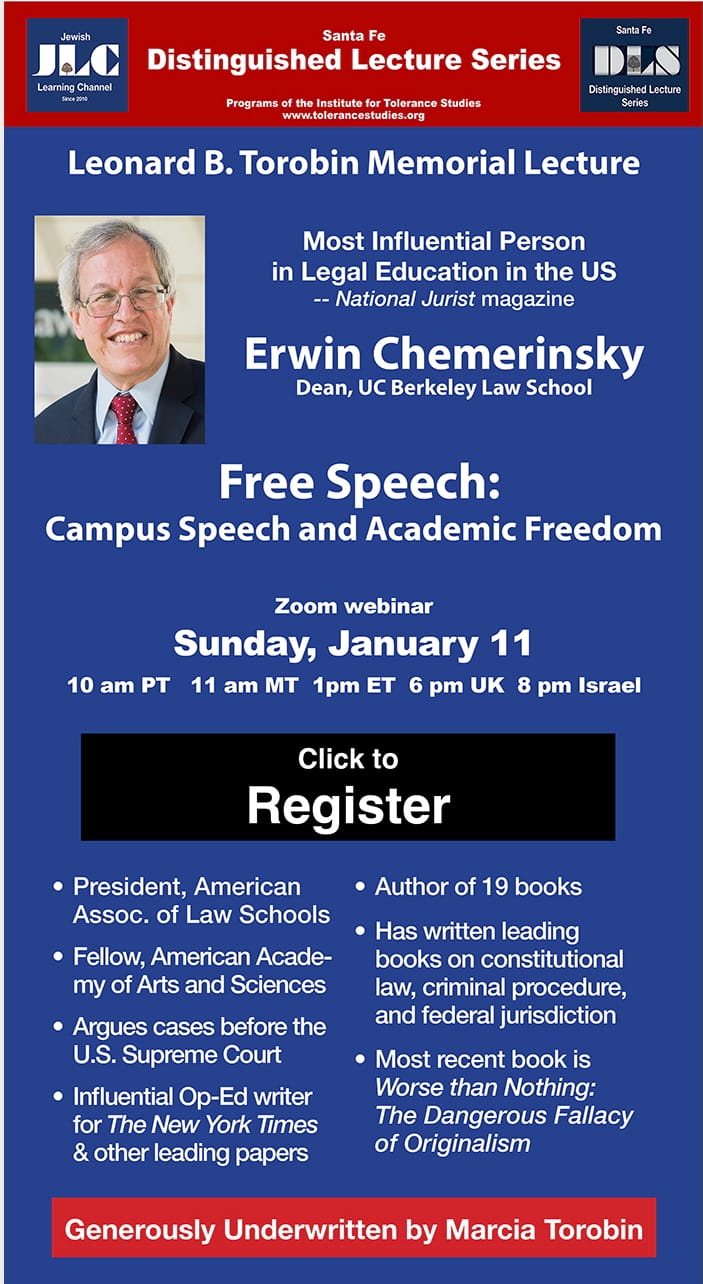

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Single Event Announcement advertisers:

Save our Jewish Cemetery

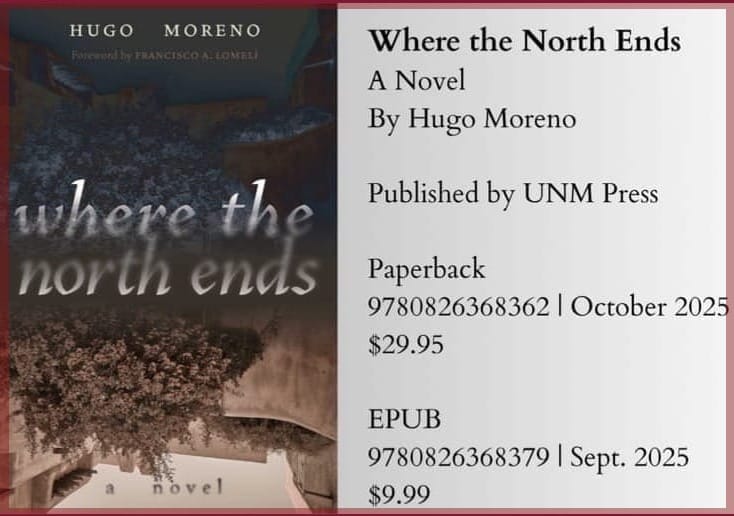

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society