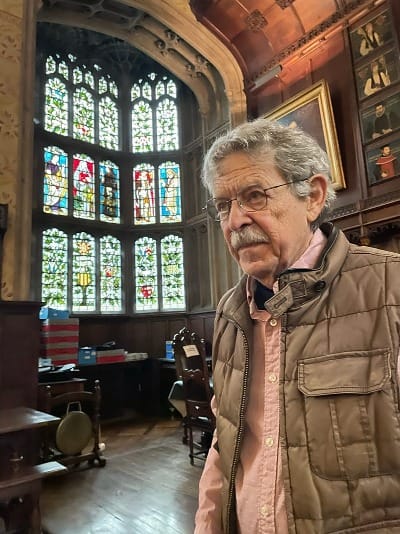

Cambridge: Where Erasmus Once Tread

by Ron Duncan Hart

February 4, 2025

Over the last twenty years my wife Gloria Abella Ballen and I have spent months on end at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge in conversations with faculty members and doing research in their vast libraries. The Bodleian Library at Oxford has an unequaled collection of Spanish Jewish medieval manuscripts, and the University of Cambridge Library has the most thorough collection of the Cairo Geniza. Oxbridge is a world unto itself. Having conversations in the ancient halls of a college dating back to 1284, remembering The Praise of Folly in the place where Erasmus once worked, seeing the original specimens that Darwin collected on his voyage on the Beagle, or being in Hawking’s college, all have highlighted the meaning of intellectual inquiry and critical thinking. Within those highlights, Erasmus’ insightful questioning of religion gone rogue has stood out as a guidestone for me, and his portrayal of Folly is etched into my mind.

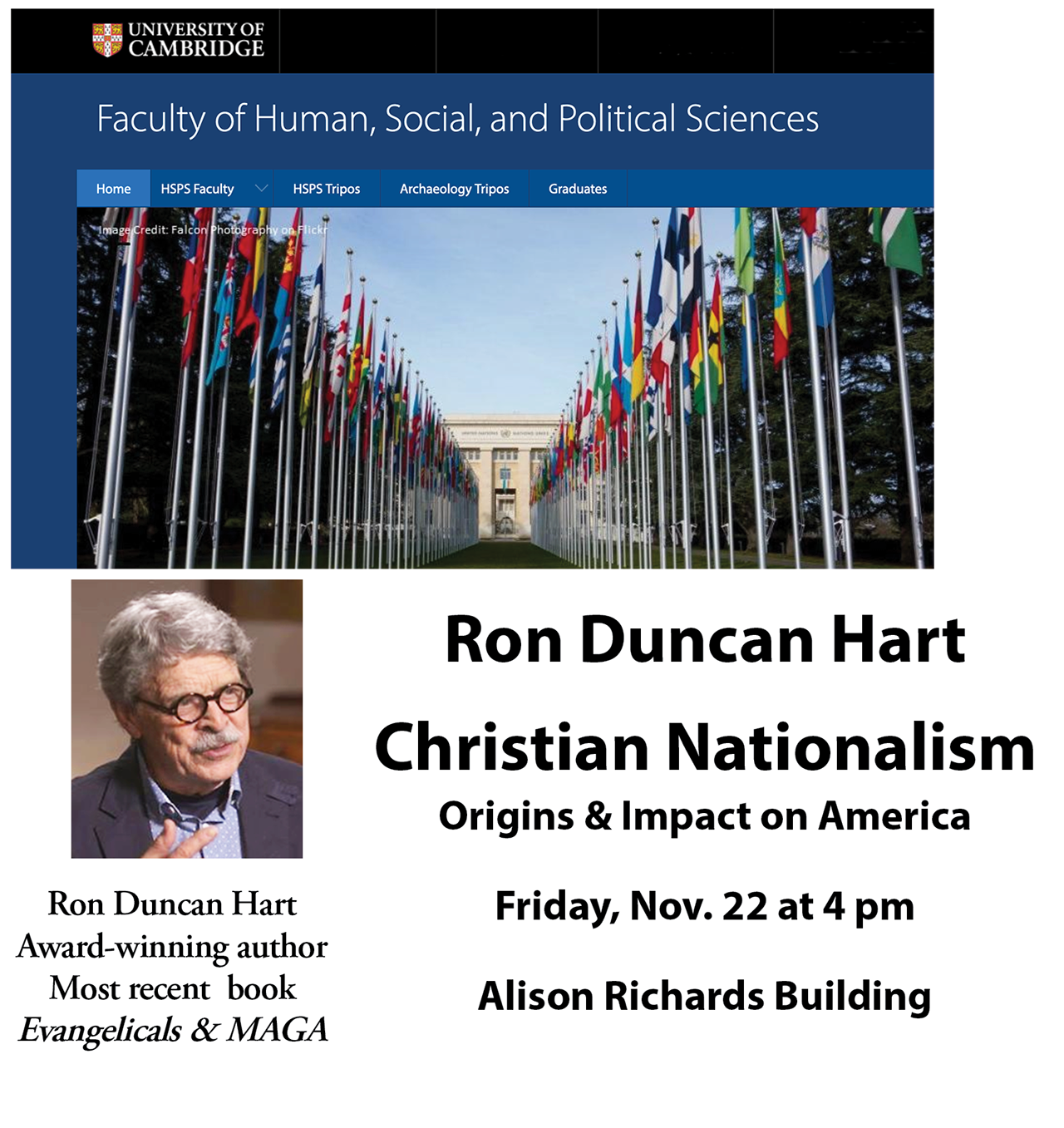

The international resurgence of religion-based nationalism in recent years has brought me back to Erasmus and his critical insights about corruption resulting from the fusion of religion and political power. When I was asked to speak in the Faculty of Human, Social, and Political Sciences of the University of Cambridge in November about White Christian nationalism as a political and cultural movement in the United States, I was returning to Cambridge where Erasmus once criticized the Church for losing its spiritual direction. I found thoughtful and questioning graduate students probing me about the meaning of the political surge of religious nationalism in the United States, and I gained a new perspective on this issue of the political influence of religion in my own country.

Most of the Cambridge faculty members and graduate students with whom I spoke were students of religion and politics in Europe and Africa, and as they commented on my talk, they drew parallels to the role of religion in right-wing governments in their own research. The critique made by the Russian specialists was most detailed, and they speculated whether the role of Christian nationalism in the United States would be similar to the alignment of the Russian Orthodox Church with Putin’s government. As I talked with them, they pointed out that the symbiotic relationship between Church and State in Russia under Putin has returned religion to prominence in contrast to the seventy years under the Communists. In return, the Church has given religious sanction to Putin’s policies and his projection of Russian culture and power beyond the borders of the Russian Federation, including giving its blessing to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

As we talked, they pointed out that the Church in Russia has become a full member of the power structure with Putin, who openly identifies as a Christian, reportedly with a chapel next to his office where he is said to pray daily. He wears a cross, which he has overtly promoted as having mythical properties. In exchange for the support of the Church for Putin, its teachings are now part of the school curriculum, and Church has substantial control of the popular media. Churches have been rebuilt, and religious icons are once again in favor.

Along with the sense of déjà vu in the resurgence of the Church, Jews and foreign religious groups in Russia are being portrayed as security threats to that country. As Putin has promoted this union of religion and politics, he has been making anti-Jewish comments more openly. He has used antisemitic arguments to justify his invasion of Ukraine, such as the incongruous claim that the Jewish President Zelensky is a Nazi. At the same time, he has been accusing Jews of destroying the Russian Orthodox Church, as he did recently in his end of the year press conference.

In response to these antisemitic accusations, Rabbi Pinhas Goldschmidt, the president of the Conference of European Rabbis, has warned that Putin’s “virulent antisemitism” is dangerous and characterized it as reminiscent of the historic Czarist and Stalinist antisemitism with its deadly results for Jews. The result has been a massive exodus of Jews leaving Russia in the last decade. The Russian census of 2010 showed 160,000 Jews, but the census of 2021 showed only 83,000 still living there.

Although Rabbi Goldschmidt’s warning is disturbing, I know that the United States is not Russia. We do not have a centralized Church comparable to the Russian Orthodox Church, and the antisemitism in Christian nationalism tends to be unrecognized because of its support for Israel. As the religious right gains power in the United States, we have to ask how far will it go with its religion-based WASP nationalism, and what would that mean for pluralism and non-WASP people, such as Jews?

I came away from these conversations in Cambridge thinking about the tendency toward the xenophobia of religious nationalism, whether it be Christian, Jewish, or Muslim. Jews have regularly been the first target of such governments from the medieval expulsions of Jews from Catholic countries in Europe to Russian pogroms and to Arab nationalists’ expulsions of Jews from Middle Eastern countries in recent decades. This history has shown that when religious nationalist groups gain power, they often see the Other in their midst as a foreign element that is threatening to their racial, cultural, or religious purity and has to be suppressed or extirpated.

Keeping in mind that the spiritual capacity for religious observance and practice is a rich part of our human legacy, religions have produced the best in human thought, morality, and behavioral patterns, as well as in the visual arts, literature, and music. Religious teachings have inspired us to be our better selves. But, what Erasmus pointed out 400 years ago is that when religious leaders use religion as a tool to promote their own political power and greed, they can become the villain rather than bona fide spiritual leaders we expect them to be. Religious nationalism has never bode well for Jews. Those Cambridge conversations left me with this uneasy question, “If white religious nationalists do gain access to the oligarchy of power and influence in America, what will it portend for people in our country who are different from them?”

Read author Ron Duncan Hart and his nationally award-winning series on Christian Nationalism and the Jews in the New Mexico Jewish Journal.

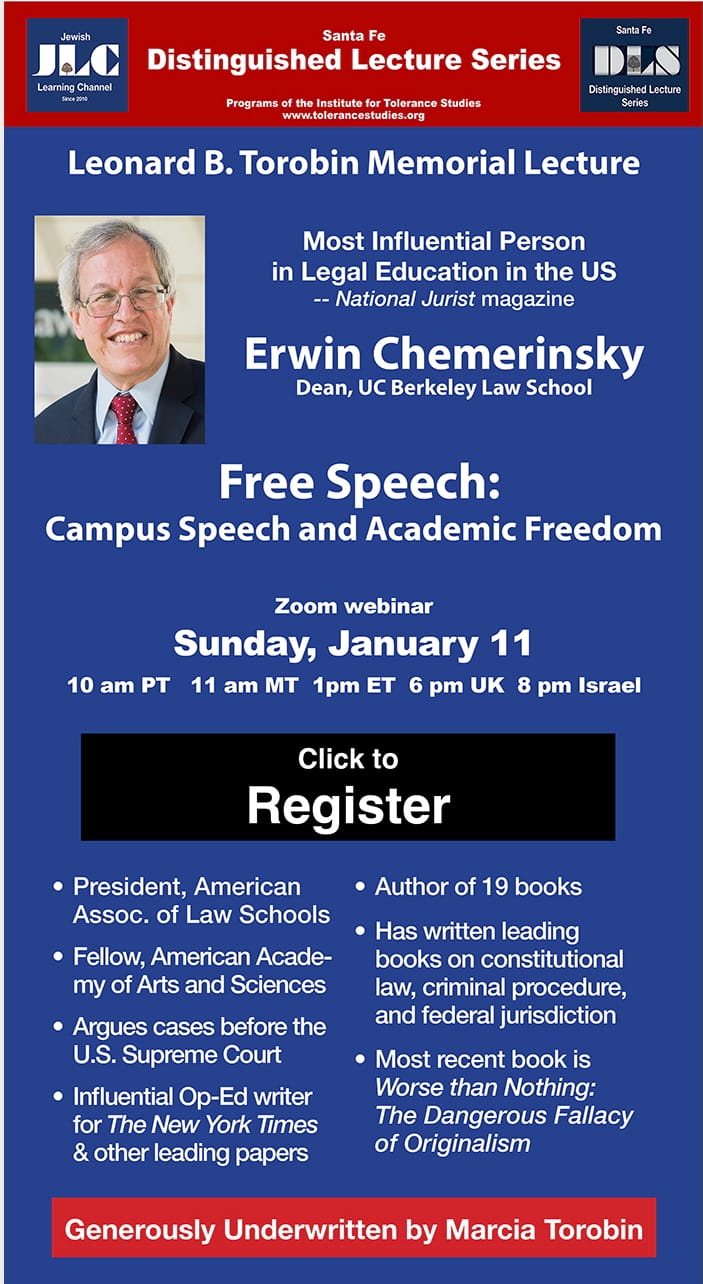

Ron Duncan Hart, Ph.D. is a cultural anthropologist and former Dean of Academic Affairs. He has awards from the National Endowment for Humanities, the National Science Foundation, Ford Foundation, and Fulbright among others. He is an award-winning author and is currently the director of the Institute for Tolerance Studies in Santa Fe and the Santa Fe Distinguished Lecture Series.

Return to HOME

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

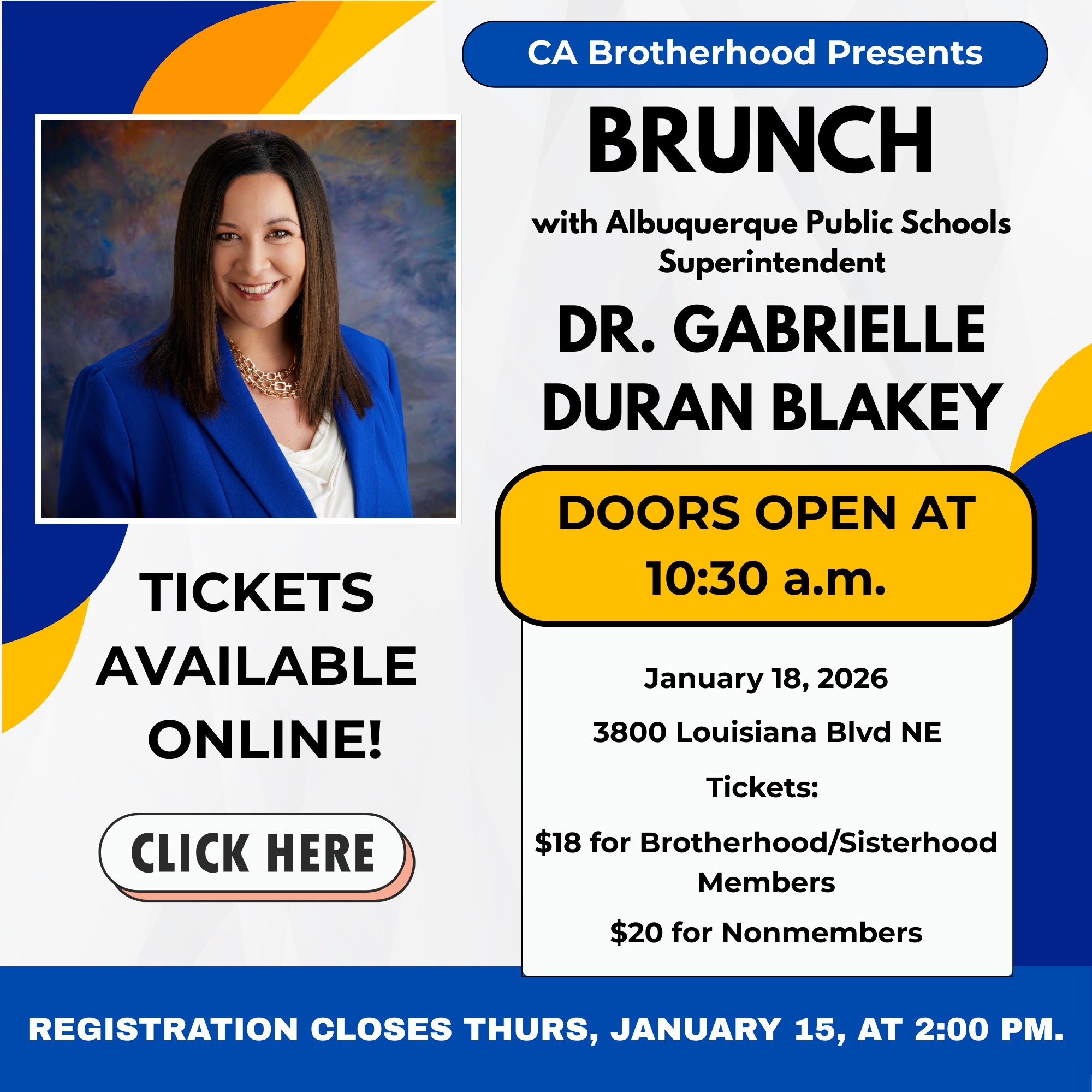

Single Event Announcement:

Save our Jewish Cemetery

Camp Daisy & Harry Stein Overnight Camp

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.