Why I Love the Talmud (and You Should Too!)

By Sarah Arrowsmith

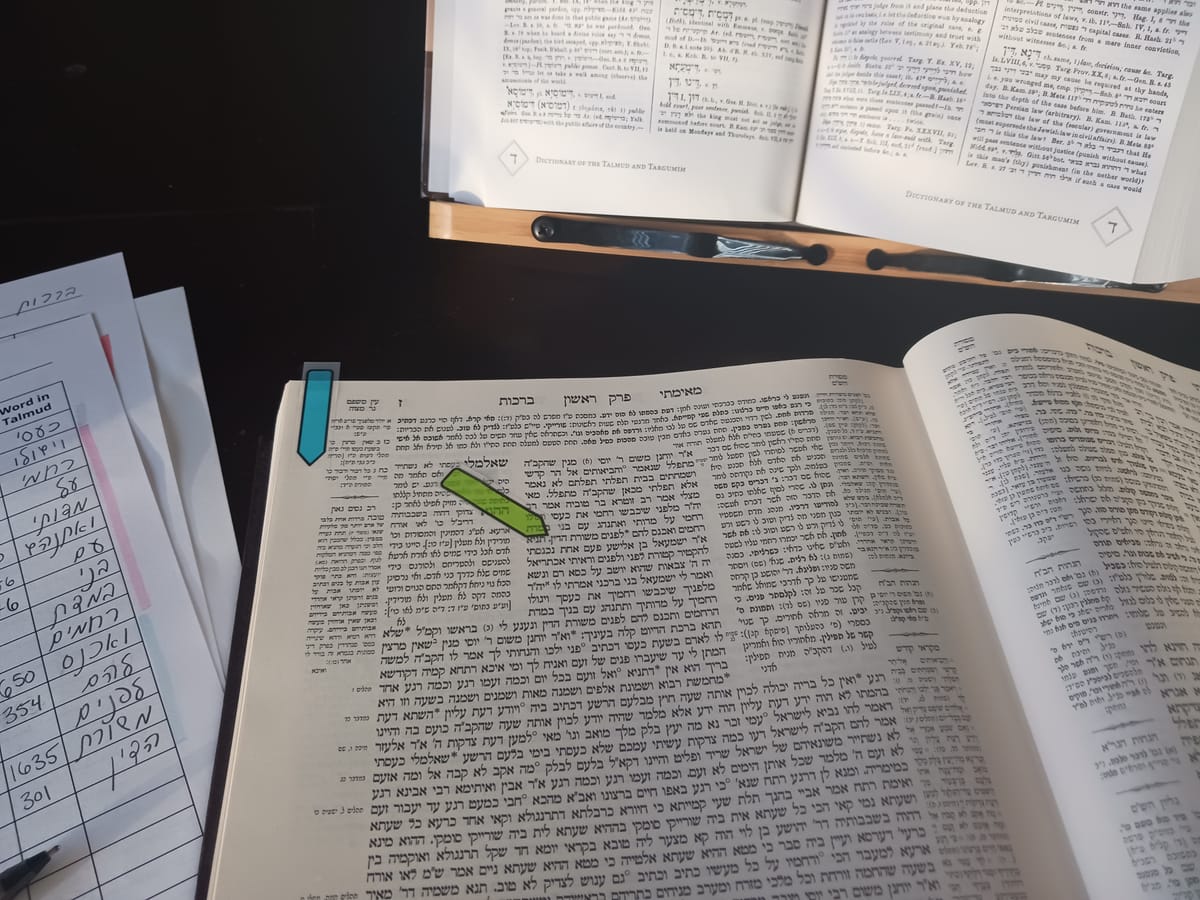

The Talmud, the core text of Rabbinical Judaism, is a long, complicated, and self-referential work. It is written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic, pulls quotes from the Tanakh without citations, and uses frequent acronyms. On a single page, you might see the mishnah and gemara, commentary from Rashi and the Tosafot, quotes from the Tanakh, and references to various Jewish legal codices. Additionally, the Talmud is 2,711 pages, which has been broken up into 63 different tractates (books). This is all to say, it is an intimidating text.

Alongside these barriers to entry, it has historically been out of reach of 51% of the Jewish community. Since the time of the Talmud, women have been barred from studying it. Rabbi Eliezer goes as far to say that the words of the Torah should be burned before they are given to a woman. Even with these prohibitions, some rich, powerful, and determined women were taught, often due to their father’s lack of sons. Today there is a booming community of women from all walks of life and backgrounds studying Talmud but there is still significant progress to be made.

The Talmud’s difficult reputation is well earned, but it is also a revolutionary and history-altering document. It arose out of a period of great trouble for the Jewish people. With the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Judaism found itself facing extinction. The sages of the time were forced to grapple with the fact that the center of religious life was gone and the Jews were exiled from Judea. There was no longer a way to perform all of the sacrifices required by G-d to remove ritual impurity and to mark holidays and major life events. Worst of all, G-d no longer had a place to live on Earth.

It was during this major upheaval that the conversations of the Talmud occurred. In this diasporic angst, the rabbis grappled with a huge breadth of topics. Some were practical such as “do diasporic judges have the ability to rule on cases equivalent to judges in the land of Israel?” Some were goofy such as “if a bag is thrown perfectly through the door of one house, exits out a back window, goes through a courtyard, and then into another house can the owner of the courtyard claim the bag as his own?” And some were desperate theological struggles of a people in crisis such as “does G-d pray, and if so for what?”

Whenever you Talmud, you are a part of these ancient conversations. You not only learn the who says what and why, you become part of an unbroken tradition of wrestling with these texts. When you recoil from Rav Huna saying that sales made by a man hanging from the gallows are valid sales, you recoil at the idea of violence being an effective bargaining tool alongside the other sages of his and future generations. When you try to understand why anybody would say such a thing, you do it in the company of centuries of Jews, including many of whom sold their own property under duress to violent antisemites.

Alongside the ancestral ties, there is a massive contemporary community of people studying the Talmud. Tens of thousands of Jews world wide participate in daf yomi, a 7.5 year long study cycle of the Talmud that has been described as “the world’s largest book club.” Even more study the Talmud at a more leisurely pace, often learning small sections as parts of classes, individually with teachers, or even on their own.

We are living in a time of unprecedented access to the Talmud. Websites such as Sefaria and AlHaTorah have digital libraries with the Talmud complete with commentaries, dictionaries, and other resources. There are countless English language daf yomi resources including podcasts, websites, and even a TikTok account. While there are already tons of resources for Talmud learning in English, all it takes for somebody to begin studying in the original Hebrew and Aramaic is knowledge of the Aleph Bet, a dictionary, and a healthy amount of chutzpah.

When studying in the original languages, you better see the nuances in specific words that are otherwise lost in translation as well as larger trends on how arguments are articulated. You can learn that the Aramaic equivalent to John Doe is a man named Ploni and that Aramaic has a word that can mean a long nap, to pile bricks, a leper, or to be cleansed; all depending on the vocalization. It gives you a better entry into the rabbinic conversations and a stronger sense of ownership of the text.

The Talmud is a stunning text. The impact it has had, the ideas contained inside, the typographical layout, and its ability to survive to the current day despite rampant antisemitism are all testaments to its unique power as a document and legacy as a living text. If you have never studied it before, I implore you to try. It doesn’t have to be your life, but with a text so large, there is something in it for everyone.

Sarah Arrowsmith is a scholar (and teacher) of Talmud. She is passionate about equitable access in education and when not wading knee deep through Jewish texts she can be found cooking, crocheting, or teaching STEAM to kids across New Mexico.

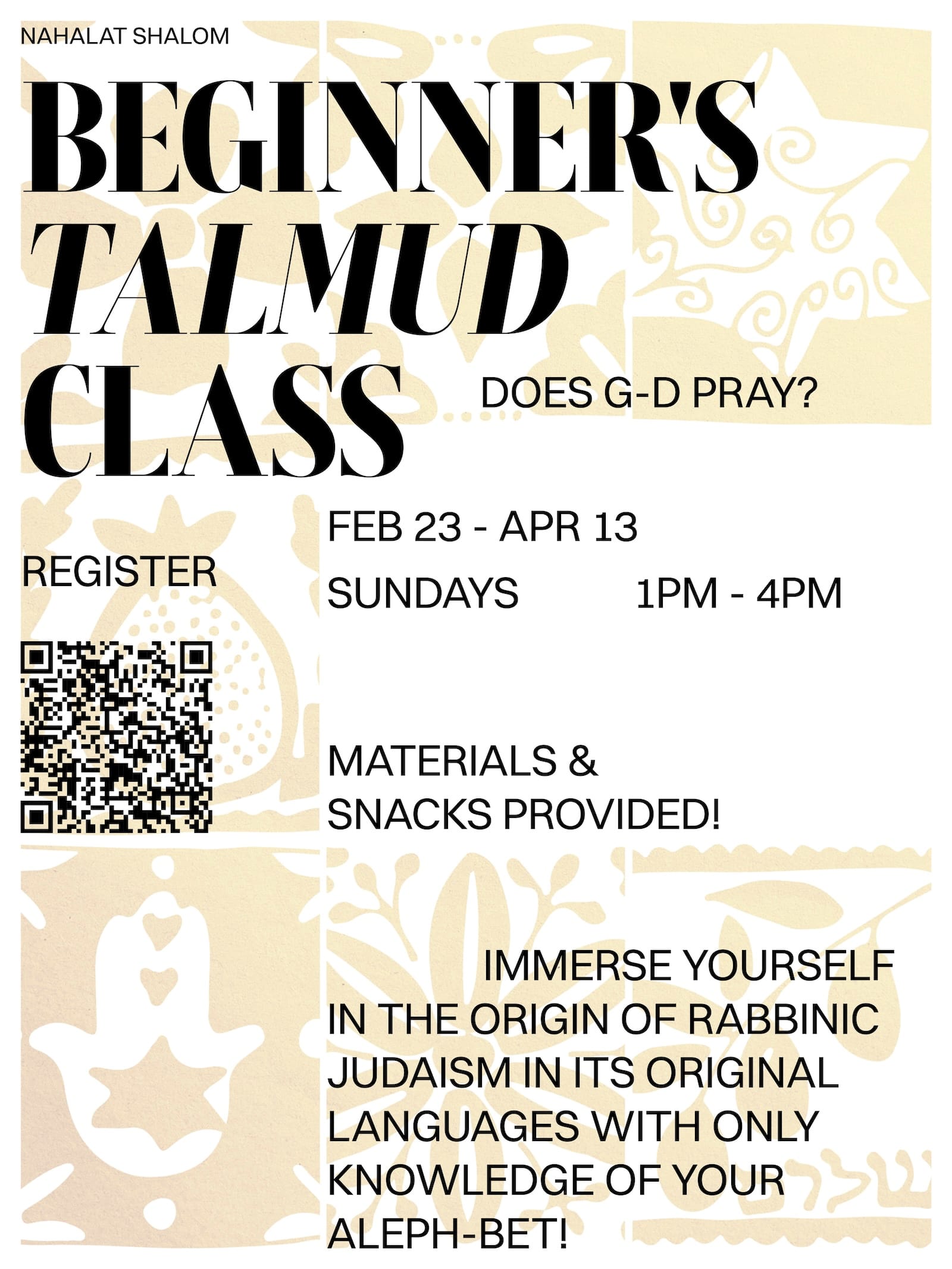

She will be teaching a weekly introduction to Talmud class on Sunday afternoons at Nahalat Shalom from February 23rd to April 6th. Registration link here.