Trauma Tourism: A Guidebook to the Holocaust

by Edie Jarolim

When I received my brown cardboard-encased review copy of the Holocaust: A Guide to Europe’s Sites, Memorials & Museums in the mail, I approached the package with a mix of curiosity and trepidation: curiosity because, as a guidebook author and editor, I was interested in the book’s format, trepidation because, as a child of Holocaust survivors, I was concerned about its content. How would such a difficult topic be handled?

This book’s arrival from England was anticipated, but the package invoked the memory of a volume that turned up unexpectedly when I was a teenager. Wrapped in plain brown paper, it was addressed to my mother and bore a European return address I didn’t recognize. Instead of tearing off the paper as I’d expected, my mother left the package unopened on the coffee table of our Brooklyn apartment for weeks. There was something ominous about the way she avoided it, as though its mere presence in our home was dangerous, as though it exuded toxic fumes.

In a way it did.

A typical self-absorbed high schooler, I badgered her to open the package. She refused, and wouldn’t explain why.

One day, when I came home from class, it was gone.

I demanded an explanation. My mother replied tersely that the book contained lists of Jews who had died in a concentration camp; I don’t know now which one. She had been afraid to find out if those lists included her parents who had been deported from Vienna to meet an unknown fate, one my mother didn’t care to contemplate. That they didn’t make it out of Austria alive was enough for her to bear; who needed the specific, horrific details? Finding no familiar names on the list, my mother threw the book out. End of story.

The tendency to keep secrets and avoid painful truths was characteristic of both my parents. Like my mother’s family, my father’s relatives had been wrenched from their everyday lives in Vienna by the Nazis. My parents rarely talked about the events of the Holocaust in anything but the most general terms, alluding darkly to death camps. My sister and I assumed that, except for an uncle and a couple of cousins in Europe that we’d never met, we had no living relatives.

“Don’t ask, we won’t tell” was the family motto.

***

Years later, when I joined a therapy group for children of Holocaust survivors, I came to understand that every traumatized family is traumatized in its own way. Some group members’ parents talked incessantly about the past; others, like mine, locked their experiences away in a box. My father had died by then but, as the result of probing that was gentler than my heavy-handed demands for information in the past, I learned a bit more about my mother’s family, including the fact that one of her uncles, Siegmund Kornmehl, owned a butcher shop that shared an address with Sigmund Freud for 44 years.

Still, my mother remained reticent about the past. It wasn’t until a decade after she died that I took up the search for information again, this time through a genealogy blog, Freud’s Butcher. Perhaps in keeping with the family tradition of avoiding painful topics and — to put a more positive spin on it – in order to learn more about my cultural inheritance, I went on a quest to learn more about the lives, rather than the deaths, of my ancestors. In doing so, I found an astonishing number of living relatives.

Which brings me back to the Holocaust guidebook. Author Rosie Whitehouse acknowledges:

"I had mixed reactions from people when I told them I was writing this book. Some people were surprised as it is a new and novel idea to look at the Holocaust in this way…Others welcomed it as a way to tell so many untold stories, but some people thought dark tourism like this seemed a rather odd thing."

She admits that “Holocaust tourism has had a bad press recently with reports of people taking inappropriate selfies at the site of mass murder—but put that on one side for a moment.”

Browsing through the book, I naturally turned first to the Vienna section. I’ve visited the city several times in recent years and read extensively about its Holocaust history. I can say without hesitation that the listings for the city are comprehensive; although Whitehouse says the book is “hugely selective,” I can’t think of any relevant site that is omitted. This is especially impressive given the scope of the book, which covers all of Europe.

But the Holocaust framework looms like the angel of death over everything, even sites that can be enjoyed from a different perspective. Take the listing of the Sigmund Freud Museum, the tourist attraction with which I am most familiar. The author starts off by stating: “To get a feeling for the rich cultural contributions that the Jews made to Viennese culture, visit the home of psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud…the Freud family were among 110,000 Austrian Jews who managed to escape.” We then learn that Freud’s neighbors and the 76 Jews detained in the building between 1939 and 1942 are memorialized with names recorded in the stairwell, and that Freud’s four older sisters died in death camps.

However Sigmund Freud is not merely a representative of Jewish cultural contributions, not just a “psychoanalyst,” as the blurb asserts. Casting him in this role diminishes his historic importance. And it is not made clear that the museum itself is a testament to Freud’s forced exile from Vienna. Visitors expecting to see the famous couch will quickly learn that it and all the exotic tchotchkes Freud’s residence was known for are now in London’s Freud Museum—and understand why this is the case. Why not give potential visitors a better idea of what they will see when they visit and respect the museum’s own terms of engagement with the topic?

Another example of the overemphasis on what is lost, not what remains, is the listing for the Jewish Museum. One of the few specific exhibits mentioned, a “Hanukkah menorah,” is contextualized by reference to the deportation and death of its owners. When I visited, one of the things I enjoyed seeing was Andy Warhol’s portrait of Sigmund Freud, part of the artist’s series of “Ten Portraits of Jews of the 20th Century.” Another was a photograph of the Hakoah women’s swim team, which reminded me of how much my mother loved the water; I hadn’t realized swimming was part of her Viennese heritage.

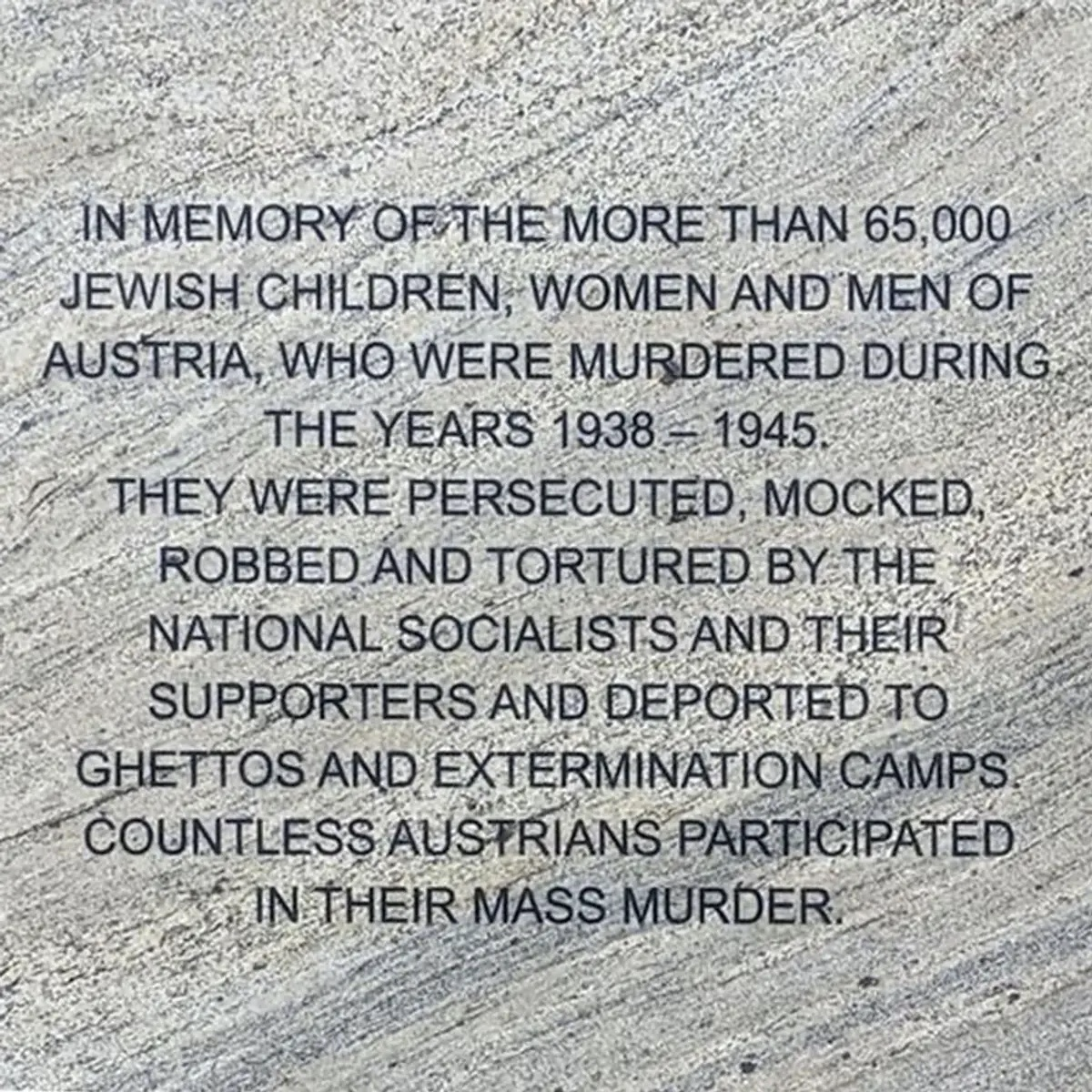

Although I understand why the author would want to place these more neutral sights – that is, ones that are not intrinsically related to the Holocaust – in the larger framework of the guide, there is more than enough death to ponder in sites that would not exist without the attempted Final Solution. One example is Vienna’s Shoah Wall of Names Memorial. In this case, I would wish for more context, not less. I have no basis for comparison with other Holocaust memorials throughout Europe, so am left wondering if this one was unique in its strong indictment of Austria’s role in deporting Jews, a statement that is not quoted or described in the guide’s listing:

I also browsed the book for sites outside of Austria directly associated with murdering, rather than commemorating, Jews, such as Poland’s Auschwitz, where my paternal uncle Richard died, and the Rumbula forest outside of Riga, Latvia, where his sister (and my namesake aunt Edith) was likely shot. These are places I would not visit. I’m with my mother on that and, as far as I could tell, this book never again takes up the set-aside question of people taking selfies at these sites.

But, as I said, every traumatized family is traumatized in its own way. I know relatives of Holocaust victims who have gone to the camp where their ancestors died in order to pay their respects. This guidebook outlines what they will see when they visit, though it can’t predict how they will react.

And that’s not to suggest everything in this book is grim – or impersonal. Throughout, there are monuments to resistance fighters, tales of heroism, and moving survivor stories. And though I thought I was well versed in Holocaust history, there were several surprises for me. For example, I never knew that the Haganah had headquarters in Vienna. Nor was I aware that there had been a plan to settle Jews in what was then the French colony of Madagascar. Hitler’s frustration when it could not be implemented because of France’s resistance led to the attempt to carry out the far more dire Final Solution.

All in all, this book provides an excellent historical overview of Holocaust-related events, including a timeline and detailed maps, one in full color, as well as comprehensive historic introductions to each area that it covers. It certainly fulfills its mandate to educate as one of the Bradt “Travel Taken Seriously” series of guides.

According to the author, the book is for travelers “in search of a specific story – in this case the Holocaust.” Such a traveler “will discover much about what Europeans choose to remember, what they prefer to forget and how they have thought about what happened to their Jewish neighbors over the decades.” While it is hard to imagine anyone undertaking a journey sufficiently comprehensive to learn more than a small piece of that story, it is easy to see this as a good fit for the serious armchair traveler—and one who might plan a trip based on the parts of the book that sparked their particular interest.

Admittedly, the timing of this book’s publication, a year after 10/7, has colored my opinion of whether the book can achieve its stated goal of telling a historical story. While it provides irrefutable proof that these events occurred, this past year’s dramatic rise in antisemitism has made it clear that Holocaust deniers are going to Holocaust deny, facts notwithstanding. And practitioners of Holocaust inversion – the claim that the Jews (er, Zionists) are now doing in Gaza and Lebanon what the Nazis did in Europe – will look to the book as confirmation that the Jews have “learned nothing” from their horrific experiences.

For this reason, in my life and in my blog, I’ve turned my attention to current events. Decades from now, I don’t want there to be another guidebook full of monuments to dead Jews. And I definitely wouldn’t want it to contain testimonials from diaspora Jews who had to escape or be rescued because they closed their eyes to the signs of what was happening all around them until it was too late.

Edie Jarolim is a widely published freelance writer and editor. She is the author of four travel guides, a dog guide, and a memoir. Her articles about Jewish topics have appeared in Tablet Magazine and The Forward and on her Jewish genealogy blog, FreudsButcher.com.

Return to HOME or Table of Contents

Community Supporters of the NM Jewish Journal include:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Temple Beth Shalom

Congregation B'nai Israel

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

Single Event Announcement:

Save our Jewish Cemetery

New Mexico Jewish Historical Society

Policy Statement Acceptance of advertisements does not constitute an endorsement of the advertisers’ products, services or opinions. Likewise, while an advertiser or community supporter's ad may indicate their support for the publication's mission, that does not constitute their endorsement of the publication's content.

Copyright © 2024-2025 New Mexico Jewish Journal LLC. All rights reserved.