Seeds of a Good Year: Black-Eyed Peas for Rosh Hashanah

By Claudette Sutton

Photos by Charles Brunn

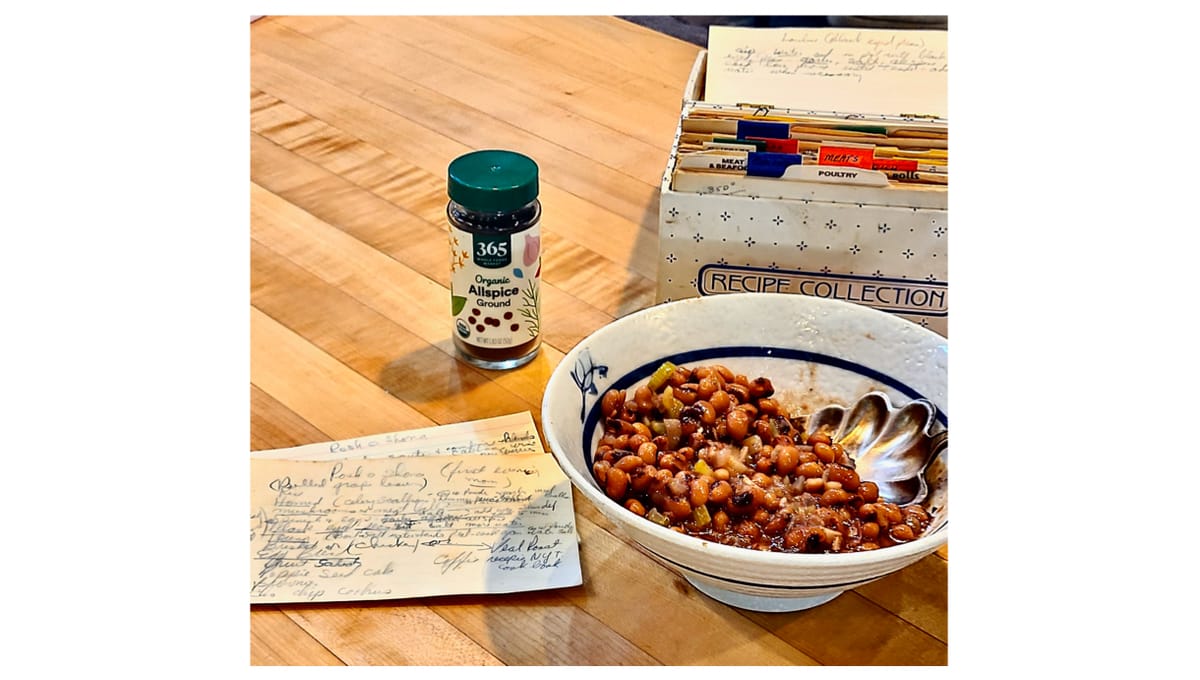

Shortly after my mom died, my brother and his wife sent me a wonderful gift: Mom’s recipe file. Nothing brings Mom back quite like seeing those 4x6 index cards with her handwritten recipes and crazy spelling (Rosh a Shona?!). The little blue and white file box is like a time capsule, taking me back to some old favorite foods plus a few that haven’t stood the test of time. (Remember Harvey Wallbanger Cake? Me neither.)

I particularly love the section of Mom’s holiday and party menus. I think of these as notes she slid into bottles and tossed into the ocean, trusting them to float back to herself in a year. Mom was a fabulous cook, widely remembered as a warm and welcoming hostess, but her anxiety in the planning stage typically went through the roof. Looking at those menus as an adult, I have a better sense why. Here’s just some of the foods listed on her menu for the second day of Rosh Hashanah: rice, hamud, mushrooms and meat balls, black-eyed peas, tongue, veal roast or brisket, fruit salad, and a few baked desserts – all to fill the bellies and spirits of 15 or 20 people spanning four generations. I’m stressed just thinking about it!

Here’s what Mom did not have to worry about: Harvesting the barley. Planting the wheat. Vine tending. Ploughing the fields. Drought.

Mom’s harvest came reliably from Giant Food and the kosher butcher. And yet whether she knew it or not, Rosh Hashanah, like most other holidays on the Jewish calendar, are to this day pegged to the agricultural cycle of ancient Israel. Alongside whatever religious or historical significance we might have learned about Jewish holidays in religious school, those holidays also align with the seasons and growing cycles of the Middle East.

Knowing just a little about this and curious to learn more, I called Rabbi Min Kantrowitz of Albuquerque (one of those women who seems to know a lot about everything). Why had the Jewish holidays been timed around the agricultural calendar way back then? And why has that alignment persisted, well into post-diaspora times, when so many Jews live far from the Middle East and may never have tilled a field or threshed wheat?

“One of the pieces of genius of the Jewish calendar was the decision to keep the holidays in sync with the agricultural seasons,” Rabbi Min told me. “In contrast with the Muslim calendar, in which Ramadan can fall in summer or winter, you’re never going to have the fall harvest holiday of Sukkot falling in February.”

The task of aligning the lunar Hebrew calendar with the solar year is incredibly complicated, she said, but the result (at least in the Northern Hemisphere) is an alignment between the holidays and the seasons. “The whole holiday cycle is partially agricultural and partially religious.”

For example: “Passover falls right around the harvest of the barley,” she said. “Barley was considered an animal food, not a human food, but people at least had barley until the wheat ripened.”

The counting of the Omer – the number of days after the second night of Passover – begins on the evening of the second seder and continues for 49 days, just as the wheat comes in.

“The Omer begins with the reaping of the barley and culminates with the holiday of Shavuot, exactly as the wheat is ripening,” Min explained. “The wheat harvest was, in ancient times, the most important for the health of the community. If your wheat crop failed, you’d starve. That whole period when wheat was growing was a time of great anxiety and lots of prayers for agricultural success.”

Shavuot happens also to be when we celebrate the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai, Min noted, coinciding our most important spiritual harvest with the most vital agricultural one.

When Rosh Hashanah rolls around a few months later, we start a new calendar year just as we are reaching the culmination of the summer harvest and beginning a new growing cycle. The ritual foods of the holiday – pomegranates, apples, dates, black-eyed peas – are all fruits of the harvest, combining symbolic meaning with seasonal timeliness.

I wondered how this tracking of Jewish religious holidays with the agricultural seasons of ancient Israel would affect us if we lived in Scandinavia, or the Arctic, or Bali – places where the climate has little overlap with Greater Israel. Or the Southern Hemisphere, for that matter.

“Wherever we happen to be in the world, we’re still aligning ourselves with the agricultural calendar of the Middle East,” Min said, “since the roots of Jewish practice were in the land of biblical Israel. Wherever we are on the planet, we have connections between the foods of our ancestry, our spiritual calendar, and our rhythms today.”

Did Mama feel this connection, perhaps in some deep internal place of knowing, as she planned her holiday menu? I can’t say how conscious this was, but I can see it in the foods she put on our table, from recipes she inherited and sometimes adapted from her parents and ancestors.

One of the recipes on her menu every year was lubieh – black-eyed peas – a standard Rosh Hashanah dish on a Sephardic table. Like the seeds of a pomegranate, black-eyed peas represent fruitfulness and plenty, a culinary invitation to good fortune. They are also delicious.

Legend has it that the custom of eating black-eyed peas (in the form of Hoppin’ John or other dishes) on New Year’s Day in the American South was adopted from early Spanish and Portuguese Jewish immigrants. The first Jewish colonists in the Southern US arrived in Savannah, Georgia, in 1733.

Whatever their historical, spiritual, or metaphysical significance, black-eyed peas are an easy and tasty dish to add to your Rosh Hashanah – or any – menu.

Black-Eyed Peas (Lubieh)

1 small onion, diced

2-3 cloves garlic, minced

3 tablespoons oil

2 stalks celery, diced

1 tablespoon tomato paste

2 cups dried black-eyed peas, soaked overnight, OR 2 15.5-ounce cans

1 teaspoon kosher salt

1 teaspoon allspice

Black pepper to taste

Sauté the onion and garlic in oil until soft. Add the diced celery, black-eyed peas, tomato paste, salt, pepper, and allspice, with about a half cup of water. Bring to a boil, then cover and cook on a low flame just until tender, about 20-30 minutes for dried black-eyed peas, 15-20 for canned, adding a little water if necessary to keep from drying out.

Claudette Sutton is the author of Farewell, Aleppo: My Father, My People, and their Long Journey Home and a regular contributor to the New Mexico Jewish Journal. She loves helping family stories come into the world and is available as a freelance editor or coach for your writing project. Visit her at https://www.claudettesutton.com/

Return to HOME or Table of Contents

Community Supporter Advertisers of the NM Jewish Journal:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Temple Beth Shalom

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Congregation B'nai Israel