Make Room for This One: The Eucalyptus Cookbook

By Claudette Sutton

Photos by Charles Brunn

You’ve said it, I’ve said it, we’ve all said it: Why do I need another cookbook? I don’t have room for more, I’ll never use all the ones I already own, and can’t I find everything I need on the Internet now anyway?

I’m here to tell you, you’ll want to find room for one more: The Eucalyptus Cookbook by Moshe Basson.

Basson is the owner and chef of the world-renowned Eucalyptus Restaurant, located just outside the walls of Old Jerusalem. Born in Iraq in 1950, he immigrated to Israel with his parents at 9 months old, growing up with the brand-new country. His recipes reflect his family’s Mizrahi background, Arab neighbors, Ashkenazi influences, biblical foods, local crops and wild-foraged native plants – a mix that reflects Israel itself.

The book is full of sumptuous photos and mouth-watering recipes, with ingredients you’ll recognize from other Middle Eastern cookbooks, configured in new ways, like Chicken Makloubeh, Beetroot Kubbeh, Almond Garlic Soup, and Fish Kebabs with Preserved Lemon Cream.

Some dishes go further afield, like Purslane with Tahini, Sorrel Soup, Mallow Gnocchi, and others, made from wild plants commonly found in backyards and roadsides not just in Israel but throughout the US.

One of my favorite parts of the book – the “secret sauce,” you might say – are the essays that preface each dish. Drawing from Basson’s family experiences, biblical anecdotes, food science, psychology and history, they create a sense of context and conversation that enrich the the meal.

I was particularly curious about one of those essays when I spoke to Basson recently via Zoom, from his home in Modi’in, between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, with his dog Carmen by his side.

In “Of Salt and Precision,” Basson confesses a “mistake” he made while making his mother’s tomato-mint soup. Though he had made the soup thousands of times, it never tasted quite like hers. His mother cooked without measuring ingredients or tasting while cooking, yet her soup was not only uniformly delicious but consistent each time she made it.

In his own kitchen, Basson would taste the soup again and again in the final stages, tweaking the salt, or sugar or lemon juice, in an effort to make it as good as his mother’s. One of those times, he added a palmful (his preferred unit of measurement) of salt and, without thinking, dropped in a second palmful.

“Moshe, what are you doing! Are you sleeping? Are you dreaming?” he said, mimicking the critical voice in his head, causing Carmen to squirm. “Next time be in the kitchen when you are cooking! Don’t stay on the beach!”

And yet he was surprised to find that the soup had not become unbearably salty. It tasted good. After things like this happened again, he began to ask himself: Was there wisdom behind this “accident”? Could it explain why his mother’s food came out so delicious, and so consistent, without measuring or tasting as she went along?

In time he developed a theory that the most vital part of the cooking process happens between the nose and the brain. The scent of a simmering pot of soup or a pan of vegetables sautéing with garlic and herbs goes directly to the amygdala, the emotional center of the brain. There, it activates memories and prior associations, inviting comparisons that allow us to adjust seasonings almost automatically.

“To be a good cook, you need a palate and a memory,” Basson explained. Smell is a far more developed area of sensory intelligence than sight or sound, drawing on personal, familial, even genetic memories. We sniff our way to culinary success.

I asked Basson how he made the leap from cooking old family recipes – which seem to ask not to be changed – to creating new dishes that would make his mark as a chef.

“Most of my recipes, I got from others,” he said. “I changed this a little, I did that, and it became something new. This is how tradition is. Tradition means that you receive, and you give. You are in the middle. You are part of a chain. You don’t know where it is creation and where it’s tradition.”

With a place in the chain comes responsibility to pass on the gift, he said.

“I’m 74 and now I’m not feeling that I must be modest. Tradition means that you got, and you give. You are in the middle. You are part of this chain, so it is almost an obligation to give your recipes.

“I have come to the conclusion that there are two sorts of people. [Some] will eat a dish in restaurant or home, and they will go home and make same dish, without a recipe, maybe without the exact same ingredients, but it will taste the same. You will think the same chef made it. The other part, the majority, you can give them the precise recipe, all the hints, all the secrets, hold their hand, yet it will not be the same. So what are they missing? Now that I’m an old man, I’m trying to teach them the other part: how to involve their senses. I’m saying: Don’t follow the recipes blind, give yourself the freedom to create. In a way, forget the recipe. Fly above the recipe.”

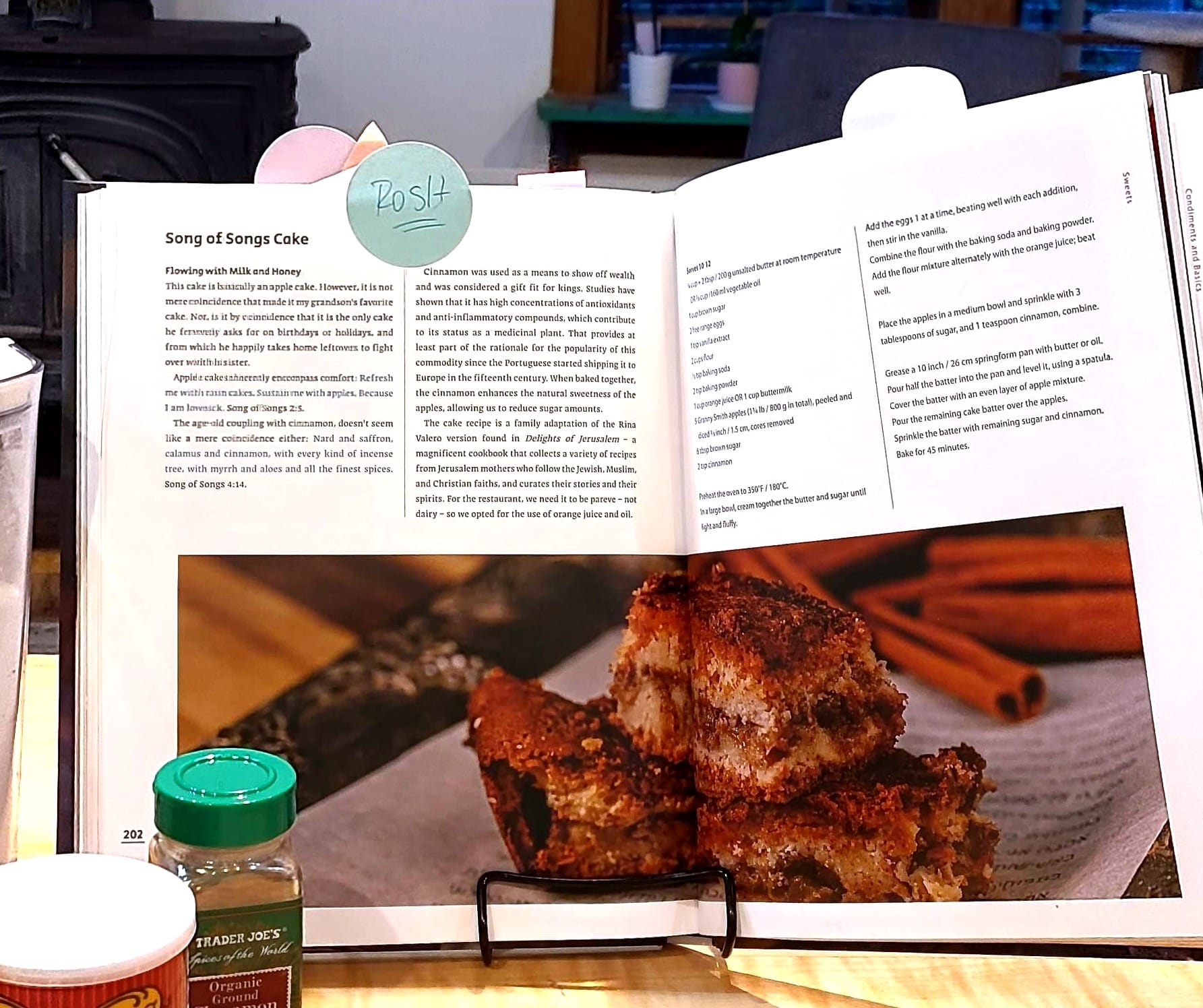

In that spirit, equipped with Basson’s recipes and his trust in my ability to fly, I plan to bring some of his dishes to my family’s table this Rosh Hashanah. Top contenders are figs stuffed with chicken, allspice, and cinnamon, and topped with tamarind sauce; and Song of Songs cake (flowing with milk and honey, of course). Who knows, perhaps I’ll make his Smoky Tamarind cocktail with mezcal, tamarind concentrate, and allspice-infused simple syrup, too! We’ll toast the idea that cooking isn’t a chemistry experiment. It’s life.

Claudette Sutton is the author of Farewell, Aleppo: My Father, My People, and their Long Journey Home and a regular contributor to the New Mexico Jewish Journal. She loves helping family stories come into the world and is available as a freelance editor or coach for your writing project. Visit her at https://www.claudettesutton.com/

Return to HOME or Table of Contents

Community Supporter Advertisers of the NM Jewish Journal:

Jewish Community Foundation of New Mexico

Congregation Albert

Temple Beth Shalom

Jewish Community Center of Greater Albuquerque

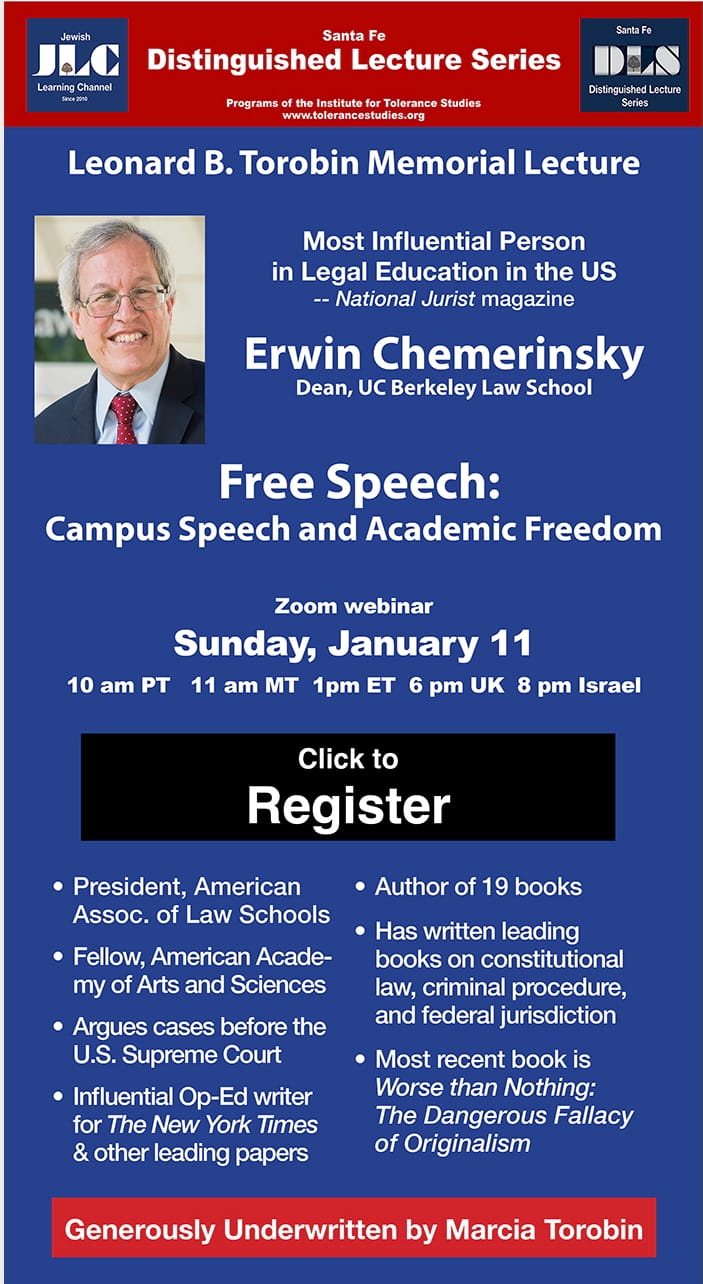

The Institute for Tolerance Studies

Shabbat with Friends: Recapturing Together the Joy of Shabbat

Jewish Federation of El Paso and Las Cruces

Congregation B'nai Israel